[from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, speech by Patrick T. Harker President and Chief Executive Officer at the National Association of Corporate Directors Webinar, Philadelphia, PA (Virtual)]

Good afternoon, everyone.

I appreciate that you’re all giving up part of the end of your workday for us to be together, if only virtually.

My thanks to my good friend, Rick Mroz, for that welcome and introduction.

I do believe we’re going to have a productive session. But just so you all know, as much as I enjoy speaking and providing my outlook, I enjoy a good conversation even more.

So, first, let’s take a few minutes so I can give you my perspective on where we are headed, and then I will be more than happy to take questions and hear what’s on your minds.

But before we get into any of that, I must begin with the standard Fed disclaimer: The views I express today are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of anyone else on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) or in the Federal Reserve System.

Put simply, this is one of those times where the operative words are, “Pat said,” not “the Fed said.”

Now, to begin, I’m going to first address the two topics that I get asked about most often: interest rates and inflation. And I would guess they are the topics front and center in many of your minds as well.

After the FOMC’s last policy rate hike in July, I went on record with my view that, if economic and financial conditions evolved roughly as I expected they would, we could hold rates where they are. And I am pleased that, so far, economic and financial conditions are evolving as I expected, if not perhaps even a tad better.

Let’s look at the current dynamics. There is a steady, if slow, disinflation under way. Labor markets are coming into better balance. And, all the while, economic activity has remained resilient.

Given this, I remain today where I found myself after July’s meeting: Absent a stark turnabout in the data and in what I hear from contacts, I believe that we are at the point where we can hold rates where they are.

In barely more than a year, we increased the policy rate by more than 5 percentage points and to its highest level in more than two decades — 11 rate hikes in a span of 12 meetings prior to September. We not only did a lot, but we did it very fast.

We also turned around our balance sheet policy — and we will continue to tighten financial conditions by shrinking the balance sheet.

The workings of the economy cannot be rushed, and it will take some time for the full impact of the higher rates to be felt. In fact, I have heard a plea from countless contacts, asking to give them some time to absorb the work we have already done.

I agree with them. I am sure policy rates are restrictive, and, as long they remain so, we will steadily press down on inflation and bring markets into a better balance.

Holding rates steady will let monetary policy do its work. By doing nothing, we are still doing something. And I would argue we are doing quite a lot.

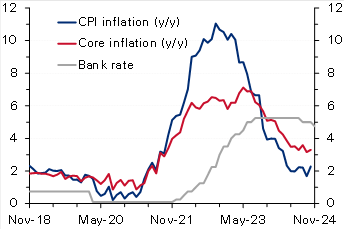

Headline PCE inflation remained elevated in August at 3.5 percent year over year, but it is down 3 percentage points from this time last year. About half of that drop is due to the volatile components of energy and food that, while basic necessities, they are typically excluded by economists in the so-called core inflation rate to give a more accurate assessment of the pace of disinflation and its likely path forward.

Well, core PCE inflation has also shown clear signs of progress, and the August monthly reading was its smallest month-over-month increase since 2020.

So, yes, a steady disinflation is under way, and I expect it to continue. My projection is that inflation will drop below 3 percent in 2024 and level out at our 2 percent target thereafter.

However, there can be challenges in assessing the trends in disinflation. For example, September’s CPI report came out modestly on the upside, driven by energy and housing.

Let me be clear about two things. First, we will not tolerate a reacceleration in prices. But second, I do not want to overreact to the normal month-to-month variability of prices. And for all the fancy techniques, the best way to separate a signal from noise remains to average data over several months. Of course, to do so, you need several months of data to start with, which, in turn, demands that, yes, we remain data-dependent but patient and cautious with the data.

Turning to the jobs picture, I do anticipate national unemployment to end the year at about 4 percent — just slightly above where we are now — and to increase slowly over the next year to peak at around 4.5 percent before heading back toward 4 percent in 2025. That is a rate in line with what economists call the natural rate of unemployment, or the theoretical level in which labor market conditions support stable inflation at 2 percent.

Now, that said, as you know, there are many factors that play into the calculation of the unemployment rate. For instance, we’ve seen recent months where, even as the economy added more jobs, the unemployment rate increased because more workers moved off the sidelines and back into the labor force. There are many other dynamics at play, too, such as technological changes or public policy issues, like child care or immigration, which directly impact employment.

And beyond the hard data, I also have to balance the soft data. For example, in my discussions with employers throughout the Third District, I hear that given how hard they’ve worked to find the workers they currently have, they are doing all they can to hold onto them.

So, to sum up the labor picture, let me say, simply, I do not expect mass layoffs.

I do expect GDP gains to continue through the end of 2023, before pulling back slightly in 2024. But even as I foresee the rate of GDP growth moderating, I do not see it contracting. And, again, to put it simply, I do not anticipate a recession.

Look, this economy has been nothing if not unpredictable. It has proven itself unwilling to stick to traditional modeling and seems determined to not only bend some rules in one place, but to make up its own in another. However, as frustratingly unpredictable as it has been, it continues to move along.

And this has led me to the following thought: What has fundamentally changed in the economy from, say, 2018 or 2019? In 2018, inflation averaged 2 percent almost to the decimal point and was actually below target in 2019. Unemployment averaged below 4 percent for both years and was as low as 3.5 percent — both nationwide and in our respective states — while policy rates peaked below 2.5 percent.

Now, I’m not saying we’re going to be able to exactly replicate the prepandemic economy, but it is hard to find fundamental differences. Surely, I cannot and will not minimize the immense impacts of the pandemic on our lives and our families, nor the fact that for so many, the new normal still does not feel normal. From the cold lens of economics, I do not see underlying fundamental changes. I could also be wrong, and, trust me, that would not be the first time this economy has made me rethink some of the classic models. We just won’t know for sure until we have more data to look at over time.

And then, of course, there are the economic uncertainties — both national and global — against which we also must contend. The ongoing auto worker strike, among other labor actions. The restart of student loan payments. The potential of a government shutdown. Fast-changing events in response to the tragic attacks against Israel. Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine. Each and every one deserves a close watch.

These are the broad economic signals we are picking up at the Philadelphia Fed, but I would note that the regional ones we follow are also pointing us forward.

First, while in the Philadelphia Fed’s most recent business outlook surveys, which survey manufacturing and nonmanufacturing firms in the Third District, month-over-month activity declined, the six-month outlooks for each remain optimistic for growth.

And we also publish a monthly summary metric of economic activity, the State Coincident Indexes. In New Jersey, the index is up slightly year over year through August, which shows generally positive conditions. However, the three-month number from June through August was down, and while both payroll employment and average hours worked in manufacturing increased during that time, so did the unemployment rate — though a good part of that increase can be explained as more residents moved back into the labor force.

And for those of you joining us from the western side of the Delaware River, Pennsylvania’s coincident index is up more than 4 percent year over year through August and 1.7 percent since June. Payroll employment was up, and the unemployment rate was down; however, the number of average hours worked in manufacturing decreased.

There are also promising signs in both states in terms of business formation. The number of applications, specifically, for high-propensity businesses — those expected to turn into firms with payroll — are remaining elevated compared with pre-pandemic levels. Again, a promising sign.

So, it is against this full backdrop that I have concluded that now is the time at which the policy rate can remain steady. But I can hear you ask: “How long will rates need to stay high.” Well, I simply cannot say at this moment. My forecasts are based on what we know as of late 2023. As time goes by, as adjustments are completed, and as we have more data and insights on the underlying trends, I may need to adjust my forecasts, and with them my time frames.

I can tell you three things about my views on future policy. First, I expect rates will need to stay high for a while.

Second, the data and what I hear from contacts and outreach will signal to me when the time comes to adjust policy either way. I really do not expect it, but if inflation were to rebound, I know I would not hesitate to support further rate increases as our objective to return inflation to target is, simply, not negotiable.

Third, I believe that a resolute, but patient, monetary policy stance will allow us to achieve the soft landing that we all wish for our economy.

Before I conclude and turn things over to Rick to kick off our Q&A, I do want to spend a moment on a topic that he and I recently discussed, and it’s something about which I know there is generally great interest: fintech. In fact, I understand there is discussion about NACD hosting a conference on fintech.

Well, last month, we at the Philadelphia Fed hosted our Seventh Annual Fintech Conference, which brought business and thought leaders together at the Bank for two days of real in-depth discussions. And I am extraordinarily proud of the fact that the Philadelphia Fed’s conference has emerged as one of the premier conferences on fintech, anywhere. Not that it’s a competition.

I had the pleasure of opening this year’s conference, which always puts a focus on shifts in the fintech landscape. Much of this year’s conference centered around developments in digital currencies and crypto — and, believe me, some of the discussions were a little, shall we say, “spirited.” However, my overarching point to attendees was the following: Regardless of one’s views, whether in favor of or against such currencies, our reality requires us to move from thinking in terms of “what if” to thinking about “what next.”

In many ways, we’re beyond the stage of thinking about crypto and digital currency and into the stage of having them as reality — just as AI has moved from being the stuff of science fiction to the stuff of everyday life. What is needed now is critical thinking about what is next. And we at the Federal Reserve, both here in Philadelphia and System-wide, are focused on being part of this discussion.

We are also focused on providing not just thought leadership but actionable leadership. For example, the Fed rolled out our new FedNow instant payment service platform in July. With FedNow, we will have a more nimble and responsive banking system.

To be sure, FedNow is not the first instant payment system — other systems, whether operated by individual banks or through third parties, have been operational for some time. But by allowing banks to interact with each other quickly and efficiently to ensure one customer’s payment becomes another’s deposit, we are fulfilling our role in providing a fair and equitable payment system.

Another area where the Fed is assuming a mantle of leadership is in quantum computing, or QC, which has the potential to revolutionize security and problem-solving methodologies throughout the banking and financial services industry. But that upside also comes with a real downside risk, should other not-so-friendly actors co-opt QC for their own purposes.

Right now, individual institutions and other central banks globally are expanding their own research in QC. But just as these institutions look to the Fed for economic leadership, so, too, are they looking to us for technological leadership. So, I am especially proud that this System-wide effort is being led from right here at the Philadelphia Fed.

I could go on and talk about fintech for much longer. After all, I’m actually an engineer more than I am an economist. But I know that Rick is interested in starting our conversation, and I am sure that many of you are ready to participate.

But one last thought on fintech — my answers today aren’t going to be generated by ChatGPT.

On that note, Rick, thanks for allowing me the time to set up our discussion, and let’s start with the Q&A.

[archived PDF of the above speech]