from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia:

Fed President Patrick Harker Says It Will “Soon” Be Time to Taper Asset Purchases

Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker told a virtual audience at the Prosperity Caucus in Washington, D.C., that the asset purchases once necessary during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic are no longer effective as a tool for supporting the economy. He also said the U.S. economy created millions of jobs in recent months, but “we just can’t fill them.”

Economic Outlook: Growth Despite Constraints

Good evening! Thanks so much for having me. I understand that when this group meets in person there is usually pizza involved — so I intend to collect on that debt next time we do this in the flesh.

I plan to offer a few remarks about the state of the national economy and the path of Federal Reserve policy. Then we can move to our Q&A, which I’m really looking forward to.

But before I do that, I need to give you the standard Fed disclaimer: The views I express today are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of anyone else on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) or in the Federal Reserve System.

Fed Structure

I know this group encompasses a very diverse crowd — we have everyone from House staffers to Senate staffers here. So, just in case anyone doesn’t know, I want to begin by giving you a very brief explanation of what, exactly, a regional Federal Reserve Bank is. Our nation’s central bank, after all, is quite unusual — unique, even — in its design.

The configuration of the Federal Reserve System — a central bank with a decentralized structure — owes its existence to the 1913 Federal Reserve Act. It is something of a testament to old-fashioned American compromise and reflects the unique demands of the United States and our economy.

The System consists of a Board of Governors, which sits in Washington, and 12 regional Banks around the country.

The Board seats seven governors, including the Chair. Each regional Bank has its own president and board of directors, which is made up of business, banking, and community leaders from the area. Fundamentally, this provides the Fed with a perspective — within each District — of the sectors and issues that make the region tick. Mine is the Third District, which encompasses eastern Pennsylvania, South Jersey, and the state of Delaware. We’re the smallest District geographically, but I like to think we punch above our weight.

The FOMC, which is responsible for monetary policy, is composed of the Fed’s governors and regional Bank presidents. Regional Bank presidents don’t always get to vote. Most of us rotate into a voting position every three years, but the governors always vote, as does the president of the New York Fed. New York, owing to the presence of Wall Street, enjoys something of a “first among equals” status within the System.

While the rest of us don’t always vote, we do always represent our Districts and play a part in the discussion. If you were at a normal FOMC meeting, you probably wouldn’t be able to tell a voting member until the end of the meeting when it’s time to raise hands. Everybody contributes.

The Fed’s decentralized nature is, in my view, a unique strength. We’re making national policy, but we’re doing it for an enormous country, and the averages of economic data can obscure realities on the ground. Conditions look very different in Philadelphia, Dover, or Washington than they do in Dallas, Salt Lake City, or Honolulu. This System gives a voice to a range of localities and sectors. It also allows us to focus on regional issues within each Bank’s District.

The United States has a unique set of needs. It’s easy to forget that we’re an outlier because we’re such a massive country: Only Russia and Canada are bigger geographically, only China and India have larger populations, and no one country has a bigger economy, at least for now. And that economy is vast, spreading across sectors and natural resources in a way that is not typical of other nations.

So, it makes sense that we have a System that feeds back information from around the country.

The State of the Economy

And what that information is telling us is that, for the past 18 months, the economy has moved in tandem with the waxing and waning of the COVID-19 pandemic. During periods when case rates and hospitalizations have declined, the economy has surged as American consumers have voted with their wallets. When COVID-19 risks abate, more Americans dine out at restaurants, check in to hotels, and fill up airplanes. Those are important categories of spending in a country where consumption makes up about 70 percent of total economic activity. In the second quarter of this year, for instance, GDP grew at a very healthy annualized rate of around 6.7 percent as case rates plummeted.

And, of course, the opposite occurs during periods when the virus spikes. When the Delta variant of COVID-19 erupted, fomenting the country’s fourth major wave of the pandemic, things started moving sideways. Consumer confidence tanked, and large industries like hospitality and leisure stagnated at best. So for this quarter, we can expect growth to come in at an annualized rate of around 3 percent, a sharp slowdown from earlier this year.

But there are reasons to be sanguine that the country’s recovery from this wave of COVID-19 may prove more durable than in the past and that we can avoid a fifth wave. And that is because more than half of the country is fully vaccinated. Getting more shots into arms will save lives and aid the recovery by reducing the size and severity of future spikes. The Delta variant has also concentrated minds: It seems to have not only persuaded more Americans to get shots on their own, but it also pushed more corporations and institutions to mandate their employees to get vaccinated. That is cause for optimism.

Filling me with less optimism is the persistent constraints the economy is operating under.

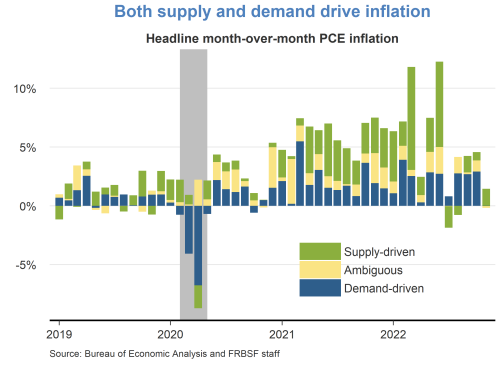

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how fragile many of our supply chains are. We’re now experiencing shortages of crucial parts like computer chips, which has hobbled not only the production of cars and trucks, but also comparatively smaller durable goods like home appliances. My recent experience attempting to purchase a printer — there were essentially none at my local electronics store — testifies to that. And good luck trying to find a new washing machine or dishwasher.

These supply chain constraints are rippling through the entire economy. Manufacturers in our region have reported having to curtail production because of difficulties securing raw materials. We’re also seeing low inventory of everything from shoes to backpacks to even chicken wings, which is a particularly troubling development as the NFL season is picking up. Unfortunately, there are indications that these constraints could persist for a couple of more years.

There’s another input lacking in supply as well, further constraining the economy: labor. It isn’t true, as was widely reported, that the economy only created 194,000 jobs in September. In reality, the U.S. economy has created many millions of jobs in recent months — we just can’t fill them. Indeed, job openings are at record highs, hitting nearly 10.5 million at the end of August. Simultaneously, more people are quitting their jobs, and the rate at which open positions are being filled is continuing to slow.

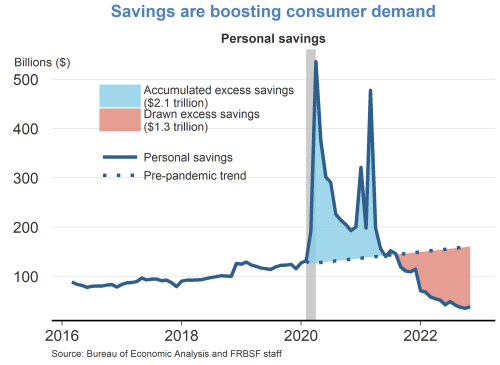

It seems that a combination of factors — trouble accessing childcare or eldercare, lingering fears about the virus, the rise in equities and home values spurring people to retire, and perhaps a general revaluation of life choices — is persuading a lot of Americans to stay on the sidelines even as the economy has reopened. And notably, the elimination of extra federal unemployment benefits has not — at least not yet — appeared to nudge people back into the workforce. I do expect that will change eventually and especially as other forbearance programs run out.

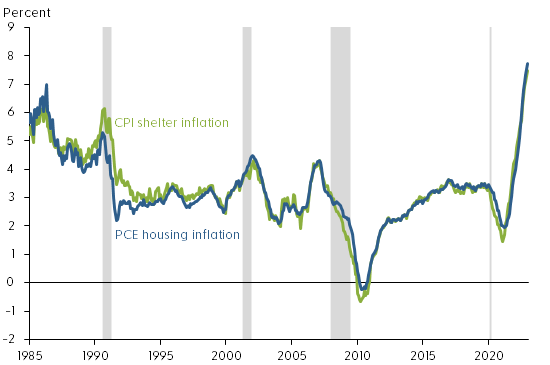

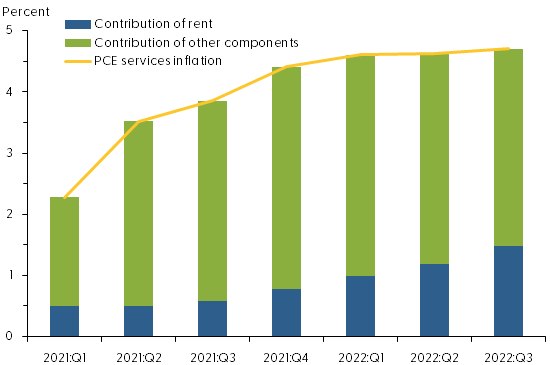

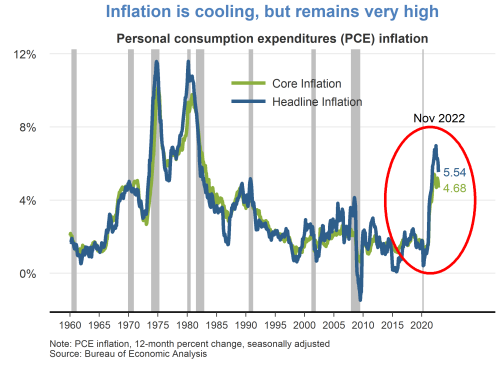

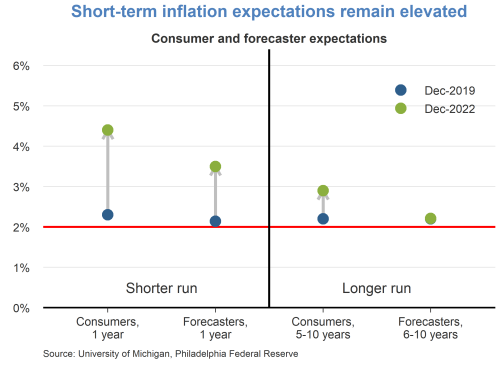

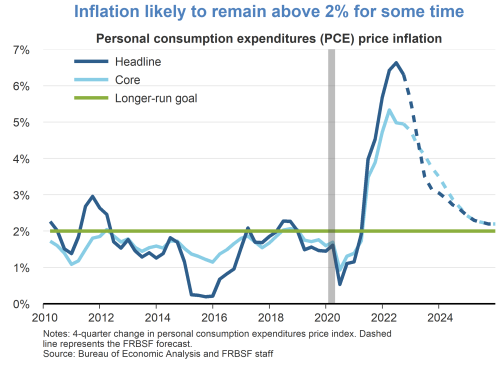

So, where does all of this leave us? For 2021, I would expect GDP growth to come in around 5.5 percent, which is a downward revision from before Delta took hold. Growth will then moderate to about 3.5 percent in 2022, and 2.5 percent in 2023. Inflation, meanwhile, should come in around 4 percent for 2021, though I do see upside risk here. After that, our modal forecast — that is, the average of all of our forecasts — calls for inflation of a bit over 2 percent for 2022 and right at 2 percent in 2023.

Fed Policy

In terms of monetary policy, I am in the camp that believes it will soon be time to begin slowly and methodically — frankly, boringly — taper our $120 billion in monthly purchases of Treasury bills and mortgage-backed securities. This comes down to the efficacy of these purchases as a tool.

They were necessary to keep markets functioning during the acute phase of the crisis. But to the extent that we are still dealing with a labor force issue, the problem lies on the supply side, not with demand. You can’t go into a restaurant or drive down a commercial strip without noticing a sea of “Help Wanted” signs. Asset purchases aren’t doing much — or anything — to ameliorate that.

After we taper our asset purchases, we can begin to think about raising the federal funds rate. But I wouldn’t expect any hikes to interest rates until late next year or early 2023, unless the inflation picture changes dramatically.

Conclusion

Given the strong headwinds facing the economy, it is a testament to its underlying strength that growth continues at a relatively robust pace. That is a tribute, as always, to the ingenuity and tenacity of our people, especially in the face of huge challenges.

Thank you very much again for having me. And now let’s move on to questions.