[from Berkeley Lab News, by Theresa Duque]

Key Takeaways

- Scientists have gained new insight into why thermal runaway, while rare, could cause a resting battery to overheat and catch fire.

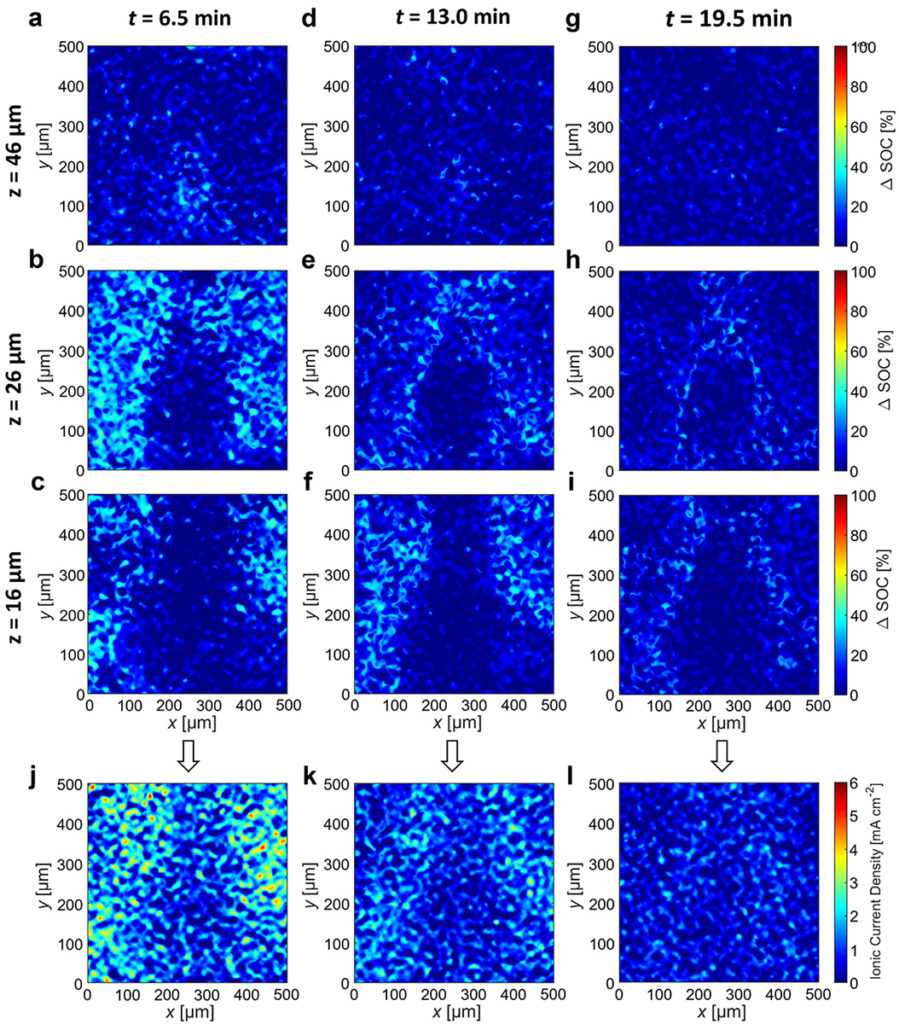

- In order to better understand how a resting battery might undergo thermal runaway after fast charging, scientists are using a technique called “operando X-ray microtomography” to measure changes in the state of charge at the particle level inside a lithium-ion battery after it’s been charged.

- Their work shows for the first time that it is possible to directly measure current inside a resting battery even when the external current measurement is zero.

- Much more work is needed before the findings can be used to develop improved safety protocols.

How likely would an electric vehicle battery self-combust and explode? The chances of that happening are actually pretty slim: Some analysts say that gasoline vehicles are nearly 30 times more likely to catch fire than electric vehicles. But recent news of EVs catching fire while parked have left many consumers – and researchers – scratching their heads over how these rare events could possibly happen.

Researchers have long known that high electric currents can lead to “thermal runaway” – a chain reaction that can cause a battery to overheat, catch fire, and explode. But without a reliable method to measure currents inside a resting battery, it has not been clear why some batteries go into thermal runaway, even when an EV is parked.

Now, by using an imaging technique called “operando X-ray microtomography,” scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and UC Berkeley have shown that the presence of large local currents inside batteries at rest after fast charging could be one of the causes behind thermal runaway. Their findings were reported in the journal ACS Nano.

“We are the first to capture real-time 3D images that measure changes in the state of charge at the particle level inside a lithium-ion battery after it’s been charged,” said Nitash P. Balsara, the senior author on the study. Balsara is a faculty senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and a UC Berkeley professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

“What’s exciting about this work is that Nitash Balsara’s group isn’t just looking at images – They’re using the images to determine how batteries work and change in a time-dependent way. This study is a culmination of many years of work,” said co-author Dilworth Y. Parkinson, staff scientist and deputy for photon science operations at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source (ALS).

The team is also the first to measure ionic currents at the particle level inside the battery electrode.

Measuring a battery’s internal currents

In a lithium-ion battery, the anode component of the electrode is mostly made of graphite. When a healthy battery is charged slowly, lithium ions weave themselves between the layers of graphite sheets in the electrode. In contrast, when the battery is charged rapidly, the lithium ions have a tendency to deposit on the surface of the graphite particles in the form of lithium metal.

“What happens after fast charging when the battery is at rest is a little mysterious,” Balsara said. But the method used for the new study revealed important clues.

Experiments led by first author Alec S. Ho at the ALS show that when graphite is “fully lithiated” or fully charged, it expands a tiny bit, about a 10% change in volume – and that current in the battery at the particle level could be determined by tracking the local lithiation in the electrode. (Ho recently completed his Ph.D. in the Balsara group at UC Berkeley.)

A conventional voltmeter would tell you that when a battery is turned off, and disconnected from both the charging station and the electric motor, the overall current in the battery is zero.

But in the new study, the research team found that after charging the battery in 10 minutes, the local currents in a battery at rest (or currents inside the battery at the particle level) were surprisingly large. Parkinson’s 3D microtomography instrument at the ALS enabled the researchers to pinpoint which particles inside the battery were the “outliers” generating alarming current densities as high as 25 milliamps per centimeter squared. In comparison, the current density required to charge the battery in 10 minutes was 18 milliamps per centimeter squared.

The researchers also learned that the measured internal currents decreased substantially in about 20 minutes. Much more work is needed before their approach can be used to develop improved safety protocols.

Researchers from Argonne National Laboratory also contributed to the work.

The Advanced Light Source is a DOE Office of Science user facility at Berkeley Lab.

The work was supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Additional funding was provided by the National Science Foundation.