from Nature Briefing:

Hello Nature readers,

Today we learn that a computer Copernicus has rediscovered that Earth orbits the Sun, ponder the size of the proton and see a scientific glassblower at work.

AI ‘Discovers’ That Earth Orbits the Sun [PDF]

A neural network that teaches itself the laws of physics could help to solve some of physics’ deepest questions. But first it has to start with the basics, just like the rest of us. The algorithm has worked out that it should place the Sun at the centre of the Solar System, based on how movements of the Sun and Mars appear from Earth.

The machine-learning system differs from others because it’s not a black that spits out a result based on reasoning that’s almost impossible to unpick. Instead, researchers designed a kind of ‘lobotomized’ neural network that is split into two halves and joined by just a handful of connections. That forces the learning half to simplify its findings before handing them over to the half that makes and tests new predictions.

Next FDA Chief Will Face Ongoing Challenges

U.S. President Donald Trump has nominated radiation oncologist Stephen Hahn to lead the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). If the Senate confirms Hahn, who is the chief medical executive of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, he’ll be leading the agency at the centre of a national debate over e-cigarettes, prompted by a mysterious vaping-related illness [archived PDF] that has made more than 2,000 people sick. A former FDA chief says Hahn’s biggest challenge will be navigating a regulatory agency under the Trump administration, which has pledged to roll back regulations.

Do We Know How Big a Proton Is? [PDF]

A long-awaited experimental result has found the proton to be about 5% smaller than the previously accepted value. The finding seems to spell the end of the ‘proton radius puzzle’: the measurements disagreed if you probed the proton with ordinary hydrogen, or with exotic hydrogen built out of muons instead of electrons. But solving the mystery will be bittersweet: some scientists had hoped the difference might have indicated exciting new physics behind how electrons and muons behave.

Contingency Plans for Research After Brexit

The United Kingdom should boost funding for basic research and create an equivalent of the prestigious European Research Council (ERC) if it doesn’t remain part of the European Union’s flagship Horizon Europe research-funding program [archived PDF]. That’s the conclusion of an independent review of how UK science could adapt and collaborate internationally after Brexit — now scheduled for January 31, 2020.

Nature’s 150th anniversary

A Century and a Half of Research and Discovery

This week is a special one for all of us at Nature: it’s 150 years since our first issue, published in November 1869. We’ve been working for well over a year on the delights of our anniversary issue, which you can explore in full online.

10 Extraordinary Nature Papers

A series of in-depth articles from specialists in the relevant fields assesses the importance and lasting impact of 10 key papers from Nature’s archive. Among them, the structure of DNA, the discovery of the hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica, our first meeting with Australopithecus and this year’s Nobel-winning work detecting an exoplanet around a Sun-like star.

A Network of Science

The multidisciplinary scope of Nature is revealed by an analysis of more than 88,000 papers Nature has published since 1900, and their co-citations in other articles. Take a journey through a 3D network of Nature’s archive in an interactive graphic. Or, let us fly you through it in this spectacular 5-minute video.

Then dig deeper into what scientists learnt from analyzing tens of millions of scientific articles for this project.

150 Years of Nature, in Graphics

An analysis of the Nature archive reveals the rise of multi-author papers, the boom in biochemistry and cell biology, and the ebb and flow of physical chemistry since the journal’s first issue in 1869. The evolution in science is mirrored in the top keywords used in titles and abstracts: they were ‘aurora’, ‘Sun’, ‘meteor’, ‘water’ and ‘Earth’ in the 1870s, and ‘cell’, ‘quantum’, ‘DNA’, ‘protein’ and ‘receptor’ in the 2010s.

Evidence in Pursuit of Truth

A century and a half has seen momentous changes in science, and Nature has changed along with it in many ways, says an Editorial in the anniversary edition. But in other respects, Nature now is just the same as it was at the start: it will continue in its mission to stand up for research, serve the global research community and communicate the results of science around the world.

Features & Opinion

Nature covers: from paste-up to Photoshop

Nature creative director Kelly Krause takes you on a tour of the archive to enjoy some of the journal’s most iconic covers, each of which speaks to how science itself has evolved. Plus, she touches on those that didn’t quite hit the mark, such as an occasion of “Photoshop malfeasance” that led to Dolly the sheep sporting the wrong leg.

Podcast: Nature bigwigs spill the tea

In this anniversary edition of Backchat, Nature editor-in-chief Magdalena Skipper, chief magazine editor Helen Pearson and editorial vice president Ritu Dhand take a look back at how the journal has evolved over 150 years, and discuss the part that Nature can play in today’s society. The panel also pick a few of their favorite research papers that Nature has published, and think about where science might be headed in the next 150 years.

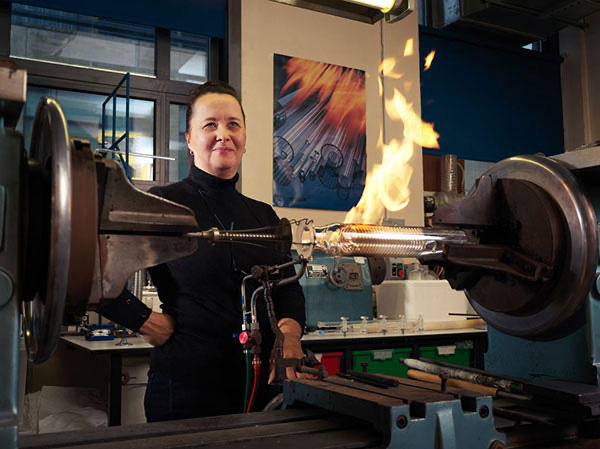

Where I Work

Quote of the Day

“At the very least … we should probably consider no longer naming *new* species after awful humans.”

Scientists should stop naming animals after terrible people — and consider renaming the ones that already are, argues marine conservation biologist and science writer David Shiffman. (Scientific American)

Yesterday was Marie Skłodowska Curie’s birthday, and for the occasion, digital colorist Marina Amaral breathed new life into a photo of Curie in her laboratory.

(If you have recommended people before and you want them to count, please ask them to email me with your details and I will make it happen!) Your feedback, as always, is very welcome at briefing@nature.com.

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing