[from India in Transition by the Center for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania, 1 September 2025]

by Krupa Rajangam & Deborah Sutton

“Oh that. We just took some undergraduate history students on board as interns. They provided the content and it was done.”

The co-founder of a digital heritage initiative promoting interactive user interfaces offered these opening remarks. Speaking at a Delhi-based museum, he had been asked about the information provided to users as they moved their hands across an interactive board, revealing images and narratives relating to the Indian freedom movement. His response clarified that the physical and digital components of such installations—for example, the 3D-modeling software and hardware, scanning equipment and its resolution and the user interface—were more carefully designed and calibrated than the content they provided.

Contemporary cultural heritage (CH) is rife with digital innovation. The COVID pandemic accelerated this transformation as archivists and curators worked to develop content that would reach remote, locked-down audiences. Within significant limits, digital platforms can democratize and facilitate access to materials previously inaccessible. Instead of being physically siloed, digitized material—as data components and not just content on culture—can be reproduced, combined, and circulated infinitely to achieve a reach previously considered impossible. Accessibility and malleability remain one of the great boons of digital formats. But here, we consider the information economy of CH practice as it exists—and not its extraordinary and often hypothetical potential—in two, overlapping realms of digitized CH: for-profit business enterprises and academic side-hustles, related to more mainstream academic research.

In the former, questions of what is shared are often less significant than the appeal of the format. In the latter, innovation is often the result of short-term projects that languish, abandoned after project completion, and rarely find audiences. Our research builds on our individual experiences and the findings of a scoping exercise examining a number of India-based heritage projects conducted in 2021-22. It suggests the need for more careful consideration of the implications of transforming CH materials into forms of data; the change impacts everything from how we understand “originality” to the reliance on for-profit services to deliver heritage material to the public.

As digitized representations of CH and access to such formats become more widespread, are we, as CH practitioners and academics, giving enough thought to how digital technologies are reshaping the nature of CH and its audience? Beyond questions of wider reach, are we sufficiently acknowledging how these changes challenge a continued focus on originality and notions of academy as primary controllers of access to knowledge and its validity, both in research and practice?

Digitizing for Dissemination

In 2019, one of us—Deborah Sutton—developed a software platform, Safarnama, including an app and authored experiences around Delhi’s CH. The project subsequently extended to Karachi. Generating “original” content, such as audio-visual clips and old photos, to be hosted on the app platform, was key to its attractiveness and usefulness, but permissions proved tricky. Some collaborators who were initially keen to contribute content quietly withdrew, likely due to the unfamiliar format and unknown reach. The app format also raised other questions. Would incorporating content from non-digital but published scholarship require authorial permission or only acknowledgement?

In 2020, Krupa Rajangam held a sponsored incubation at the NSRCEL, a business incubator located at the Indian Institute of Management-Bangalore, to develop a web interface that would host geo-locationed stories of marginalized histories by drawing on both historical facts and lived experiences. Corporate mentors remained skeptical of her ability to source “original” content on an ongoing basis, i.e., content that was both authenticated and validated. They repeatedly advised her to focus on the format, user experience, and appeal for “mass markets” so her prototype would find audiences. Both projects equally raised questions over who would consume the content and what constitutes the public or audience.

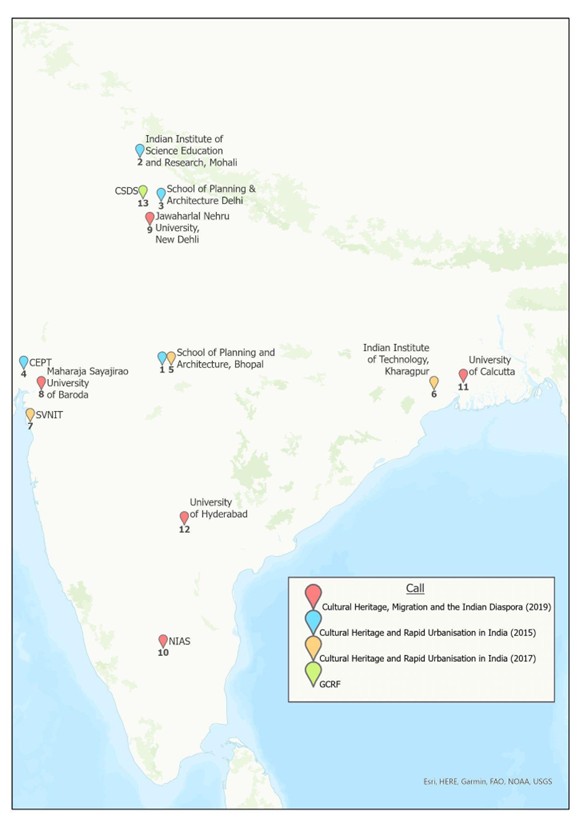

In a scoping exercise undertaken for the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), UK, in 2021-22, we explored a number of India-based heritage projects funded by the AHRC in partnership with the Newton Fund and Indian Council for Historical Research, since 2015 (figure 1). We were particularly interested in the digital components, which all projects included, even if only a website.

Our exploratory surveys firmly established the divergence in interpreting both CH and digital technologies, which was not surprising. Some projects defined and treated CH as fixed pre-existing material, to be interpreted and presented to audiences through digital technologies. Others re-framed digital formats of CH as components of data, assembling, manipulating, and representing extant archival and other materials. The rest generated digitized CH, effectively altering its nature. Typically, such projects dealt with more ephemeral or less conventional forms of CH.

Fundamental Transformations

Notions of originality remain central to art, architectural and art historical training, and CH practice. Digitization transforms the access and retrieval value of “original” material in physical archives, such as old maps and letters, much lauded in traditional “analog” scholarship, to use value as data. Once the end-user (audience) accesses this data (whether historical facts or stories), it becomes nothing more than bytes occupying valuable space, to be deleted once consumed rather than stored, making it easy to overlook or disregard the source and its context.

For example, in the Safarnama project, the app contained carefully collected and authenticated narratives on “partition memories” in Delhi and Karachi. However, the bite-sized media format meant that users would only explore content once, as snippets. This realization led the team to develop the software and incorporate the ability to download content, which at least meant that users could collect, organize and store (archive) the assembled media.

Digitization also takes away the materiality of the archive, making it more ephemeral. Non-digital materials through, and into which we render CH can (in endless combinations and cycles) be lost, forgotten, sold, recovered, collected, displayed, and stored. Such capacities of digital files are obvious, but maintaining access depends on varied and dynamic software ecologies for existence and sustained end-user access. Digital files created within one software-architecture can be incompatible with, and therefore rendered obsolete, by another. The ethos of software development is constant change.

In another paper, we examined questions of quantity, quality, and reusability of data related to digitization of building-crafts knowledge alongside CARE and FAIR principles of data management. The principles were proposed and adopted by an international consortium of scholars and industry, the former focused on responsible collection, use, and dissemination of data, especially related to vulnerable people and the latter on sustainable data management.

As an example, one AHRC project experimented with methods to capture detailed 3D images of heritage sites and structures in dynamic crowded environments. They used one set of methods to capture the interiors and another for the exteriors, hoping to merge both together and develop holistic imagery for audiences. This proved impossible at first due to issues of software compatibility. Once that was partially resolved, the new software couldn’t handle the sheer volume of data captured—and it was unclear where and for how long such volumes of data would be stored.

New realms of intellectual property remain fuzzy. While the content on digital platforms is governed by licensing and proprietary legal frameworks, it is often hosted on open platforms, through web repositories such as GitHub. Prima facie, such openness appears to challenge the proprietorial nature of archives and other repositories as keepers of knowledge. However, it raises a host of questions about how to maintain a critical understanding of archives.

Digitization may, and should, transform access but should it obliterate the regimes through which the materials were generated and organized and what’s included or excluded? For example, a local coordinator of one project that engaged with artists commented that digital technologies are typically used to document technical skills as forms of intangible heritage and develop artist encyclopedias, saying that “they are hardly used to interrogate the reality that many ‘traditional’ artists hail from marginalized castes.” Similarly, the local coordinator of another project that engaged with communities living in and around a protected heritage site commented on how digital technologies often end up being used to create a record of heritage structures without any reference to their day-to-day setting.

Any and all digital enterprise in CH, we argue, needs to integrate the ambition to use digital methods to not just present but also counter and interrogate the material, its creation, and purpose. Digital platforms and web- and app-based software are now able to manipulate and re-situate information in unprecedented ways. The novelty of such formats can displace original, provocative, and timely considerations of the material. Often, we are so taken by the visual and structural attributes of these formats, that we accept it at face value and lose sight of the tone and content of heritage as a curated message about the past and the present.

Alongside this, digital augmentations and iterations of CH, including storage, have significant financial and infrastructural implications. The creation and maintenance of digital platforms requires either developing “in-house” digital specialization or, more commonly, reliance on private, for-profit platforms. Paying for external provision introduces complexities. Funders, including the AHRC, struggle to devise guidance or policy in relation to software licensing. However, a persistent challenge to projects, and partnerships between academic and non-academic partners, is devising data and software strategies that subsist beyond the life of the funded-research project. Often, the adverse effects of the paucity of longer-term planning around IP issues, sustainability, and data archiving falls disproportionately on the non-academic stakeholder.

While digitization foregrounds the potential and promise of complete openness and equity, maybe this is lost in practice. Or digitization may merely mark the displacement of one set of ethics with another. There is a need for more careful consideration of the implications, complexities, and risks of taking CH materials out of boxes and off shelves and transforming and generating it into data files, which are, in turn, dependent on digital platforms to provide end-user access. However, the question remains of whether heritage-related disciplines are adequately prepared and willing to confront such new ways of working, which have begun to dislodge some of the privileges extant in current forms of research and practice.

Krupa Rajangam is nearing the end of her tenure as a Fulbright Fellow at the Historic Preservation Department, Weitzman School of Design, University of Pennsylvania. Her permanent designation is Founder-Director, Saythu…linking people and heritage, a professional conservation collective based in Bangalore, India.

Deborah Sutton is a Professor in Modern South Asian History at Lancaster University.